The Persian Qanat

The Persian Qanat is an ancient underground water management system used for irrigation in a desert climate.

The system is communally managed. With the use of water clocks, a just and exact distribution among the shareholding farmers is ensured. Water is transported by mere gravity. The qanat system enabled the development of settlements and agriculture.

Community Perspective: The site comprises 11 qanats, and you’ll likely bump into one when visiting other WHS in Central and Eastern Iran. Solivagant explains “How to visit a Qanat”, while Bernard details his visit to the Zarch Qanat in Yazd.

Map of The Persian Qanat

Load mapCommunity Reviews

Bernard Joseph Esposo Guerrero

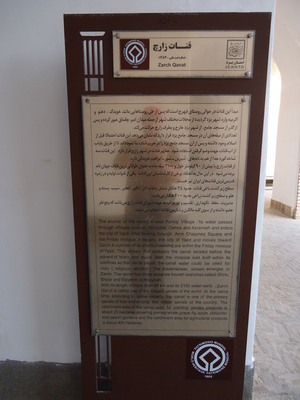

This is probably the UNESCO World Heritage Site I spent the most time in trying to understand how to “properly” visit it during my recent trip in Iran. When I was just about to give up on it, a sign suddenly emerged in the streets of the historic city of Yazd referring to the “Zarch Qanat gallery”. This seems to be an improvement since the previous reviewer went to Yazd last year (exactly 12 months apart!), reporting the glaring lack of any public information about the qanats.

Later on, my friend and I realized that there were in fact a lot of signs all over showing some sort of a direction. Only to find out that — after intently and passionately following the signs for nearly an hour — it was not really leading us to a “gallery” (i.e., an exhibit, a museum, or a showroom)! Rather, it was just illustrating where the qanat flows underneath the city! This finding was interesting, but it was far from constituting a “proper” visit.

Much to my surprise later that day, however, we eventually got the proper visit that we needed no less than inside the Great Friday Mosque itself. At the main gate of the mosque, I already wondered why there was a banner congratulating “… the successful inscription of the Persian Qanats as a UNESCO World Heritage Site”. Sadly, it obviously and shamefully fails to indicate the more important detail – that a part of the qanat can actually be accessed within it. Inside, there is a small opening on the ground that can easily be missed which leads to a payab (underground water chamber). This payab, which has been supplying the mosque the water it needs since it was erected, is one of the public openings of the Zarch qanat. The properly lit stairway goes down to some 30 meters below the ground until one reaches the well.

Surprisingly, during our two hour wandering inside the complex, despite the hoards of tourists visiting the mosque and the no lack of tourist guides around, we only saw two other curious visitors who took the effort to go down the site, and they probably were not even aware of what it is at all. Even in the walking city tour we hopped on the following day, our guide never mentioned anything about the qanats and their importance. We also learned later on that the Zarch qanat runs as well under the Emir Chaqmaq complex, but going there proved futile – there is no way to “see” the qanat.

In one of those cosy coffee shops in the city, I had a talk with its owner whom I shared my sense of achievement and pride in seeing a part of the Zarch qanat with when I least expected it. He then enthusiastically showed us a ground cover in front of his shop, opened it, and explained that it’s one of the shafts of Zarch. It was quite deep and one can hear well the flowing water!

He also told us about the ancient watermill of Koushk-e No in the neighbhorhood which is also being repaired (or prepared) at the moment to become a tourist showroom for the qanat. Furthermore, he advised that if we go there, and if we’re lucky, we might just have a peek inside. And we eventually did.

Going down through its small opening, several layers of water channels and chambers were seen. Apparently, the site lies at the crossroad of three different qanats, with the Zarch qanat specifically powering the mill. It is also interesting to know that the temperature on the ground compared to the temperature down where the waters flow can differ from 17 to 20 degrees Celsius, making it a wonderful refuge from the heat outside.

The Zarch qanat has been supplying most of the water requirements of the desert city of Yazd for more than 3,000 years already. It also happens to be the longest qanat in Iran at 120 kilometers in length. In its entire course, from the mother well (water source) to the farmlands it irrigates, more than 2,000 shafts have been constructed. Indeed, qanats are a proof that ancient Persians were masters in hydraulic engineering.

The Zarch qanat definitely plays a strong role in the nomination of the Historic City of Yazd, which also has a living tradition registered in the Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in its own right. This proposal will be decided upon this coming June when the committee convenes in Krakow, Poland. I sincerely wish Yazd the best of luck.

****P.S. Albeit not among the World Heritage-listed properties, other qanats we saw in the trip include the Solomon’s spring, an exit point of a qanat that feeds water to the Fin Garden, a UNESCO World Heritage Persian Garden, and the 7,000 years old Sialk Tepe, the remains of the oldest known ziggurat, in Kashan; and the qanat that supplies water to an ancient caravanserai, refrigerator, and ice house in historic Maybod, another desert city along the Silk Road that is also in Iran’s present Tentative List for UNESCO WHS listing.

Solivagant

Before our Iran trip in Apr/May 2016 we had gained access via this Website to the “Executive Summary” for Iran’s nomination of “The Persian Qanat” (Its consideration by the 2016 WHC was of course still c2 months away). This document, which alone is 66 pages long, showed that the original T List definition for the “Qanats of Gonabad” had been significantly altered as per this Forum post.

But, even if the nomination were to be successful, we couldn’t of course be sure that all 11 nominated Qanats will get inscribed. So – which to visit? We decided to target the Qanats at Bam and Yazd.

But “how” does one actually visit a qanat?? Its very nature is as a narrow underground man-made water channel whose digging and maintenance is a dangerous job- all of which makes it unlikely “visit material”!!

The areas which were potentially to be inscribed encompass, for each Qanat

a. The “Mother Well”. This is usually deep underground since it accesses a source for the underground water. It is likely to be situated out in the country towards a mountainous area where some geological feature (sill or fault etc) has caused the underground run-off from the mountains to accumulate for “tapping”

b. The Course of the qanat – it appears that Iran has adopted the standard of nominating a 30m wide core area with the narrow tunnel underneath at its centre. This tunnel will descend very slowly gradually, getting closer to the surface along the course of the qanat as the land above also drops. Along this course will be numerous “access points”. In open country these will often be sandy mounds stretching out in a line. If you climb one of these you may see a gaping open hole/shaft (Our guide warned us to be careful of such access points since the sand in the mound around the shaft could be unstable) or, alternatively, a concrete “cap” which could be lifted to gain access – the qanat itelf could still be many meters below and require ropes etc for a descent. In towns many of the older houses will have direct access to the qanat via their own wells or steps. There are likely also to be occasional “public” access points both in the country and in the town where they will probably take the form of half domed structures covering steps leading down to water level.

c. The Exit point – by this time the qanat is going to be virtually at surface level and water will flow out into an open channel

d. An agricultural area which uses the run off water. The Executive Summary maps however show that these areas are often (always?) NOT included in the core area of the nomination but are relegated to the buffer zone or a separately described “Agricultural Demand Area”

So, in practice, that means looking for the main exit point, an accessible access point or an agricultural area which is to be included in the core!! Unless of course one is prepared to “count” as a “visit” merely having crossed/passed along the core line above ground!!

Our first search was for the Qanats of Ghasem Abad & Akbar Abad near Bam. These are situated a couple of kms south of the Arg just north of the village of Baravat. They are very short – with their core zones extending merely to 15ha each. It is noteworthy that these zones actually cross the core zone of the existing Bam inscription which extends south from the Arg to include the “fault area”. The Executive Summary justifies their inclusion for being - “… two young qanats of Bam which are extraordinary in discharge because of the roots of qanat in Baravat and Bam fault. Bam as a symbol of men’s victory over a hostile environment can also be considered as unique in his own case. The complex management of underground irrigation system in Bam leading to an unbelievable agricultural land use network in harmony with its built area.”

The photo in the Executive Summary on (PDF) page 6 of Ghasam Abad shows it as being situated far more “out in the desert” and remote from human habitation than it actually was – an example of an “old photo” being used??! The growing village of Baravat now seems largely to surround the entire line of the qanats. The exit points are situated within 10 metres of each other and are each marked by a notice in English. This was something of a surprise and may represent a part of Iran’s “nomination effort”! Gathered around the exits were a few kids and young men. The former were playing, splashing, and trying to catch little fish. One of the latter was washing his hair in the water! We asked what they knew about the possibility of a UNESCO nomination – “we had heard something some time ago but nothing seems to have happened” we were told! So much for “Community involvement”.

We followed the exit stream by having a short walk into the date palm groves which, in this case, do not seem to form part of the core zone. And that was it really. We then drove back along the line of the Qanat for a kilometre or so and reached another palm grove, at the edge of which was another notice stating that here was the “mother well” – but there seemed to be no access.

Our second Qanat “visit” was to that of Hasan Abad-e Moshir whose mother well starts south of the town of Mehriz and flows for over 40kms north into and through Yazd. Its core zone is 2759ha. One interesting aspect of its course is that it feeds Bagh-e Pavlanapour - one of the inscribed Persian Gardens. From the Executive Summary map it appears that the core zones of these 2 sites might actually touch each other. However, we had already seen 3 Persian Gardens and were due to see 3 more. We had also had a very long day and still had to get to Yazd so we gave up on the possible delights of another Persian Garden and followed the route of the Qanat south of Mehriz towards the mountains. Here we found a “public” access point where people could come and collect water. A notice in Farsi described it as being part of the Hasan Abad qanat. Steps led down around 4 metres to a rough hewn “cave” through which clear water flowed copiously. Whilst we were there, several cars drew up and their passengers filled a variety of plastic containers! Even our driver, who lived 40kms away in Yazd, where his water may well have been supplied by this very qanat joined in and got some “fresh” water. It appears that there was (and still is for those buildings which have direct access to the qanat) an entire social “etiquette” surrounding use of the shared water course within the towns such that e.g washing is only done on certain days!!

To fully appreciate the “Persian Qanat” you really need to visit the “Water Museum” in Yazd. Situated in an old mansion, it is interesting both in itself and for its fine explanations and displays. “Old fashioned” and dusty yes but who needs audio visual etc when simple displays and artefacts will do! The table top model with a “cut away” to show the course of a qanat from Mother Well to agricultural run-off both above and below ground, does the job perfectly adequately.

The museum’s additional relevance to the “Persian Qanat” nomination is that it situated directly above 2 qanats – one of which, the Zarch is Yazd’s second qanat nomination!! (see this pdf ) So, if you were so minded you could count a “museum visit” as a “Qanat visit”! In fact the qanat “on display” in the basement of the mansion is NOT the Zarch, whose location is only shown by a capping stone in the mansion’s patio. The Qanat Executive Summary isn’t clear about whether any, or if so, which, “above ground” features within towns are included in the Nomination so one must assume that the Water Museum is not included – except that it clearly sits within the “30m zone”! We may be able to discover more via the full Nomination File. The “Historical Structure of Yazd”, which will presumably include the water museum, is however due to be nominated by Iran for 2017. A busy couple of years for Yazd!! As for gaining access to the Zarch Qanat - I was unable to discover any location for the public to do so inside Yazd town – though this might of course change is it gets inscribed.

Which leaves me with the problem as to which photo to use to represent this not particularly photogenic site across more than one qanat (as insurance against the exclusion of any of them)! I have chosen a “picture package” of the sign board at Akbad Abad (as “proof” of visit!) plus the collection of water from a public access point for Hasan Abad, south of Mehriz.

Community Rating

- : Maciej Gil Fmaiolo@yahoo.com

- : George Gdanski BH Dutchnick Afshin Iranpour

- : Pablo Tierno Palimpsesto Alexandrcfif

- : Wojciech Fedoruk Solivagant Richard Stone Thomas Buechler Stanislaw Warwas Alexander Parsons Michael anak Kenyalang Reisedachs Chalamphol Therakul Bernard Joseph Esposo Guerrero

- : Szucs Tamas Jean Lecaillon Joyce van Soest Zoë Sheng Martina Rúčková Javier

- : Wieland

- : Tony H. Carlo Sarion

- : Ivan Rucek

Site Info

Site History

2016 Advisory Body overruled

ICOMOS proposed Deferral

2016 Revision

On T List as "Qanats of Gonabad"

2016 Inscribed

Site Links

Connections

The site has 10 connections

Constructions

Geography

Human Activity

Timeline

Trivia

WHS Hotspots

WHS Names

World Heritage Process

Visitors

74 Community Members have visited.